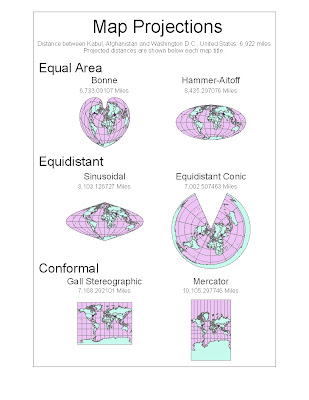

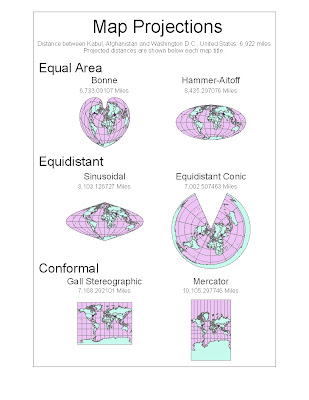

Map projections are necessary because a three dimensional sphere, like Earth, cannot be flawlessly represented on a two dimensional map. When we try to represent the Earth on a flat surface, distortions occur which could be deceiving to the map reader. However, maps are able to preserve certain features, such as direction, distance, or area. This makes particular maps better for specific purposes than others. Three map projection categories that I have included in my ArcGIS project are equal area, equidistant, and conformal. Depending on what the map is being used for, each of these categories could be beneficial. When looking at the distance between two cities, such as between Washington D.C. and Kabul, Afghanistan in my project, different results will be yielded based on the type of projection used. Some projections exaggerate the distance by almost double. This is one example of why map projections matter when doing spatial analysis.

The first two maps on my project are equal area projections. An equal area map is made so that one square kilometer drawn on one portion of the map is equal in area to a square kilometer drawn on another portion. The Bonne projection is a pseudoconical equal area map projection. It has a slight heart shape, and on the central meridian and standard latitudes shapes are not distorted. The other equal area map on my project is the Hammer-Aitoff. Hammer created this equal area map based on Aitoff’s equidistant map. One aspect of the significance of an equal area map is that it does not exaggerate the sizes of continents relative to each other. This could be important because for political purposes, political leaders could choose a map projection which makes their country look gigantic compared to another country, when in reality the countries are close to the same size. It could be used as propaganda to advocate going to war against another country. Thus, the map projection could be purposely used to deceive the viewer. When relative area is an important aspect of a map, an equal area projection is a useful tool.

The next map projections are equidistant, a map that is centered so that any distance from the central given point is an accurate representation of the distance from that point. Distance is not preserved from any point on the map, but only to the one or two control points. One type of map projection that can be classified as equidistant is the Sinusoidal projection. This is equidistant in the respect that the true distance between two points on the same meridian corresponds to the distance on the map between the two parallels. Another equidistant projection is the equidistant conic projection. On this map the meridians are all equidistant, straight lines which converge at a point, and parallels are arcs of circle, in which distortion is constant along the arc. One significant feature of an equidistant map is that you can compare your distance to other places on the Earth, if you were located at a control point on the map. This could be helpful in determining the shortest route to take if you were on an airplane. Equidistant maps in my project were fairly accurate in projecting the distance from Washington D.C. to Kabul, Afghanistan, even though neither city was a control point on the map. The equidistant conic projection gave the most accurate distance between the two cities of any projection featured in my project.

The final map type represented in my projection is conformal. On conformal maps, angles are preserved locally. This means that a small area can be rendered in its true shape. These maps use grids of longitude and latitude. They do not preserve area or distance, but give a good general picture of the Earth. One example is the Gall Stereographic projection. While temperate countries are shown well on this projection, its vertical stretch creates a large amount of distortion at the poles. This would make this map a poor choice for analyzing how much remaining habitat there is for polar bears. Another example is the Mercator projection, which also greatly distorts the size of land near the poles. The significance of this map is that it is useful for nautical purposes due to its ability to preserve local angles. The linear scale is constant in all directions around a point.

The map projection that is most useful for a specific purpose depends on what is trying to be shown by the map. Equal area, equidistant, and conformal map projections are all useful for certain purposes, but can be misleading if used for other purposes due to distortion. In order to determine the utility of a map, we must be able to understand the implications of the distortions. While these distortions may be dismissible on a small scale, when looking at the world as a whole the distortions are magnitudes larger. By looking at the distance between Washington D.C. and Kabul, Afghanistan on each map projection, it is clear that the distortions really do matter.

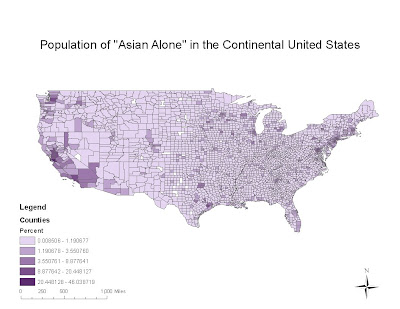

The counties with the highest percentage of Asians are primarily located on the west coast. Seattle, the San Francisco Bay area, and the Los Angeles region all have relatively high proportions of Asian Americans. There is also a relatively high proportion of Asians in the New England region. The tendency of having a high proportion of Asian Americans seems to be linked with major cities. This is likely due to the fact that many Asian Americans immigrated to the United States for the purpose of working in industrial areas, and the spatial trend today still reflects that.

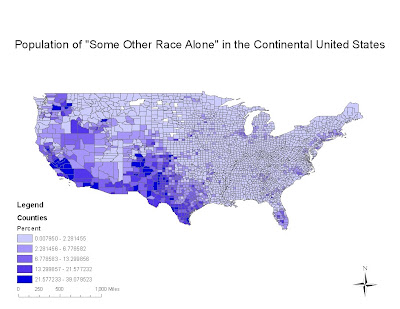

The counties with the highest percentage of Asians are primarily located on the west coast. Seattle, the San Francisco Bay area, and the Los Angeles region all have relatively high proportions of Asian Americans. There is also a relatively high proportion of Asians in the New England region. The tendency of having a high proportion of Asian Americans seems to be linked with major cities. This is likely due to the fact that many Asian Americans immigrated to the United States for the purpose of working in industrial areas, and the spatial trend today still reflects that.  Counties with a high proportion of people classified as "Some Other Race Alone" are primarily located in the southwest. Along the Mexican border on the southwest, there is the highest occurrence. This is likely due to the high proportion of Hispanic people of Mexican nationality in the region that do not consider themselves to be any of the other races listed. Counties that do not directly border Mexico but are still nearby also have high percentages of this category. The percentage decreases spatially from south to north in the western United States. The rest of the United States has low percentages of people in this category.

Counties with a high proportion of people classified as "Some Other Race Alone" are primarily located in the southwest. Along the Mexican border on the southwest, there is the highest occurrence. This is likely due to the high proportion of Hispanic people of Mexican nationality in the region that do not consider themselves to be any of the other races listed. Counties that do not directly border Mexico but are still nearby also have high percentages of this category. The percentage decreases spatially from south to north in the western United States. The rest of the United States has low percentages of people in this category.